As the entertainment industry

shifts its distribution strategy

to let people buy or rent movies closer to—or simultaneously with—their release in theaters, you may find yourself amassing a larger digital library than you’ve had in the past. But when you buy a movie from a digital service like Amazon Prime Video or

Vudu

, does it really belong to you? What if you buy a song on iTunes or download one to your phone from Spotify? Are these files yours forever? If you cancel the service or, as unlikely as it may seem, one of these huge companies goes out of business, what then?

The answer is a little complex, but the short version is, no, you don’t actually own the digital media files that you purchase. This doesn’t mean you’re imminently at risk of losing every digital movie and TV show you’ve ever bought at the whim of a megacorp, but it is possible. Here’s what you need to know.

What it means to “own” digital content

What do we mean, exactly, when we talk about owning something digital? Everybody knows—or hopefully everybody knows—that it doesn’t mean you can turn around and sell that digital item to someone else, broadcast it, or otherwise distribute it en masse. You don’t need to dig far into any terms-of-service agreement to find such actions expressly forbidden.

For this discussion, to own a digital file is to be able to watch or listen to that content anytime you want, with no further payments, in perpetuity—or at least as long as you can get a device to convert that ancient 4K video file into something that your brand-new holodeck on your space yacht can read.

By that definition, well, you still don’t own anything. Not really. What you’re purchasing in most cases is a license to watch that video or listen to that song. Effectively that license is good for as long as it really matters. I mean, let’s be honest: If an 8K sensurround remaster of

The Lord of the Rings

comes out in 2030, are you going to care about the 1080p version you bought on Vudu?

Let's take a look at the

FandangoNow/Vudu terms of service

, which are fairly typical. I’ve bolded the important parts.

Pretty standard stuff. You can watch the item as often as you want, but the terms specify that you can’t “sell, rent, lease, distribute, publicly perform or display, broadcast, sublicense or otherwise assign any right to the Content to any third party.” You probably already know this: Just because you purchased and downloaded a movie doesn’t mean you can burn it to a DVD and sell the DVD—among other reasons, because you would have to crack the digital rights management on the file, which is also expressly forbidden. Digital rights management, or DRM, allows a company to restrict what you can do with a digital file, such as preventing copying or permitting you to watch it only a certain number of times.

In the FandangoNow/Vudu terms of service, there is one additional section worth looking at, under “Viewing Periods”:

The “including Fandango/Vudu Purchased Content” part is the big one. What this means is that if Disney, for example, decides it doesn’t want to allow Vudu to sell its movies anymore, the company can have Vudu turn off Disney movies. Unlikely as that may be, theoretically the service could block access to movies you’ve already purchased—as the terms state, “[Y]our ability to stream or download Content may terminate if our licenses terminate, change or expire.”

Here’s how

Amazon says the same thing

. Again, the bold emphasis is mine:

A case about this

is working its way through California courts

.

And here is

Google’s version

, for media content sold through its Play store:

Interestingly, Google says that it may offer you a refund if it deletes your content without asking.

How likely is any of this to happen? Not very, which we’ll discuss in a moment.

Here’s what you definitely don’t own

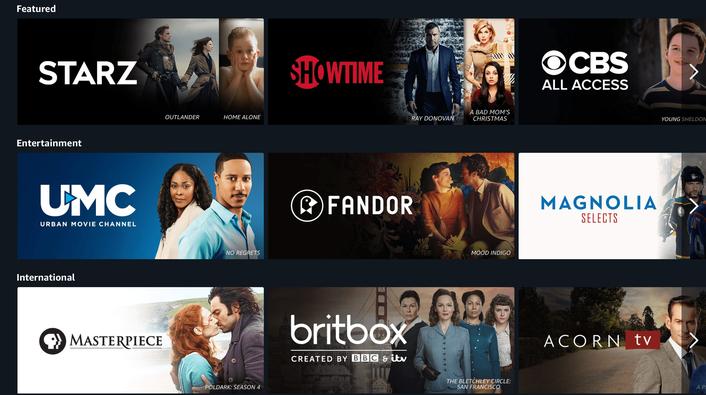

There is some media content that you are absolutely, flat-out renting. On the music side, Spotify is a good example. If you cancel your subscription, you no longer have access to any files you’ve downloaded to your phone. Your subscription lets you lease these files, with no option to buy. The music industry loves this arrangement, by the way, as you’re continually paying to listen to the same songs, albeit a fraction of a penny each time. I’ve singled out Spotify, but all streaming music services are like this—in contrast to download services such as iTunes or Amazon Music (see below).

Streaming video, obviously, is another category in which you don’t own anything, even if you download content to watch on your mobile device or computer. For example, if you cancel your Netflix service, anything you’ve downloaded gets locked out, just as with Spotify. The same with

Disney+’s Premier Access

. Even though you’re paying a price that’s closer to a purchase fee (usually $30), it’s still more like a rental that’s accessible only as long as you keep your Disney+ subscription.

Going one step further, if you go to a different country, even if you’re just on vacation, you might get locked out of content you could watch in your original country. A

VPN

might help with that by geoshifting your location; then again,

it might not

.

So what does this all really mean?

It’s unlikely that any corporation would willingly nuke the presumed assets of millions of customers, despite how much these companies might love for you to buy all your movies yet again. The backlash would be substantial, and the resulting lawsuits would likely take years and millions of dollars to resolve. Corporations, for the most part, would be reluctant to alienate and anger such a huge customer base.

That’s not to say it couldn’t happen. Just take the squabbles between

Roku and Warner

, or

Roku and Google

, as two of many examples in which consumers are forced to deal with the fallout between bickering companies.

A more likely scenario is that a media company goes out of business. In this case the most probable course is that some other corporation buys up the digital-media portion of the business and carries over your right to watch the content you bought. This already happened with Vudu, which was owned by Walmart for over a decade and is now owned by Fandango Media, a corporation itself owned by NBCUniversal and WarnerMedia ... which are owned by Comcast and AT&T, respectively.

But if you’re still worried about losing access to your purchased content, the solution is to go physical. It’s a lot harder for companies to stop you from watching a physical disc, though that has been

tried in the past

. Although digital rights management is built into Blu-ray and DVD players and receives periodic updates via the web, if you don’t connect the player to the web, it should be able to continue playing any compatible disc format. Some discs even come with a code that unlocks a digital copy, which is certainly convenient—though as we’ve discussed, you can’t expect those copies to last forever (most discs even have a date by which you need to activate the code).

Audio is even easier. Shocking as it may seem, you can still buy CDs. Rip them to a hard drive, and you have digital copies for as long as your hard drive lasts (and presumably, the CD will last even longer). Alternatively, you can buy and download DRM-free music and convert it to whatever file format you like or trust. iTunes and Amazon Music files are DRM-free, as are the downloads from many smaller music sites, many of which offer even higher-quality audio files. For older music downloads that have DRM, you can typically convert them to a DRM-free format such as FLAC or WAV.

So, no, you don’t own your digital files, and theoretically you could at some point be prevented from watching or listening to them. In reality, your digital collection is probably safe for the foreseeable future—but if the very idea of a company locking you out of your movies and music makes you angry, we suggest embracing physical media such as 4K Blu-rays and CDs, which will likely survive any digital-media apocalypse.