Harvard geneticist George Church has co-founded a new company with an audacious goal: engineer an elephant that resembles the extinct woolly mammoth. The company, named Colossal, aims to use woolly mammoth DNA to make a hybridised Asian elephant that could thrive in Arctic climates.

Using these hybrids, Colossal’s long-term goal is to convert swaths of today’s mossy tundra into the grassy steppes they once were during the Pleistocene epoch, the period of multiple ice ages that ended 11,700 years ago. Some scientists hypothesise that at large scales, this reversal could reduce future climate change by slowing the thaw of Arctic permafrost. Along the way, Colossal hopes to create new—and lucrative—biotechnologies, including tools that would supplement traditional conservation approaches.

“We’re de-extincting genes, not species,” Church says. “The goal is really a cold-resistant elephant that is fully interbreedable with the endangered Asian elephant.”

The idea of using biotechnology to help endangered species, or even extinct ones, is not new. In 2009 researchers successfully cloned a subspecies of ibex that had died out in 2000, though the clone lived for only a few minutes. In April, the San Diego Zoo and California-based nonprofit Revive & Restore announced they had cloned an endangered black-footed ferret, with the goal of adding genetic diversity back into captive-breeding programs.

And for years, Church’s plans to “resurrect” a mammoth using the extinct titan’s sequenced DNA made headlines around the world.

“Most of the science had been solved; they just needed that funding and focus,” says Colossal co-founder Ben Lamm, a serial entrepreneur who most recently founded the AI company Hypergiant. “It’s kind of exciting—after two years of working on this—to start to tell people what we’re doing.”

Don’t expect pseudo-mammoths to arrive anytime soon. Colossal’s plans rely on several technologies that are unproven in elephants. Even on the company’s most aggressive timeline, Church says that Colossal’s first hybrid calf is six years away. A self-sustaining herd could take decades to establish.

But even at this early stage, Colossal’s mission raises profound questions about what it means for a species to be extinct—and how biotechnology can and should be used to address today’s extinction crisis. With Colossal’s arrival, the conversation is no longer abstract, says Tori Herridge, a mammoth biologist at the Natural History Museum in London. “My initial reaction was one of like, Shit’s getting real,” she says.

Welcome to Pleistocene Park

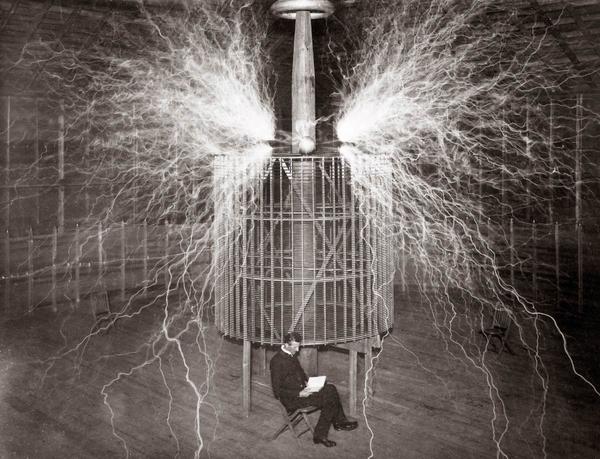

Church’s dreams of engineering a hybrid mammoth first deepened after an interview he did with the New York Times in 2008 about efforts to sequence the woolly mammoth genome.

At first, the idea was more of a grand intellectual puzzle. But in the years that followed, Church started to collaborate with Stewart Brand and Ryan Phelan, the founders of the California-based Revive & Restore. Brand and Phelan aim to use biotechnology to help shore up threatened species and to bring back extinct ones.

“De-extinction and the idea of what we call genetic rescue is really a story about hope and being able to repair some of the damage that humans have caused over the centuries,” says Phelan. “It’s not nostalgia—it’s really about increasing biodiversity.”

Brand and Phelan invited Church to the world’s first conferences on “de-extinction,” held in 2012 and 2013 at the Washington, D.C., headquarters of the National Geographic Society. (National Geographic Partners, which produced this article, is a joint venture between The Walt Disney Company and the nonprofit National Geographic Society.)

At these meetings, Church met Sergey Zimov, a Russian ecologist and director of the Northeast Science Station in Cherskiy, in the Republic of Sakha. Since the 1980s, Zimov has studied Siberian permafrost and has sounded the alarm on the vast amounts of methane and carbon dioxide that could seep into the atmosphere as it thaws.