When Colonial Pipeline was hit by ransomware on May 7, 2021, it paid 75 bitcoins to restore its systems. But the money was not entirely lost. The FBI was able to trace it as it jumped from one digital wallet to another. At one point, on May 27, 63.7 of the bitcoins were transferred to an address and stopped moving. The FBI got the private key to unlock that bitcoin wallet and was able to retrieve the funds.

The seizure was a big win for the U.S. Justice Department's ransomware task force, dedicated to investigating and disrupting cybercriminal gangs. Ransomware crippled more than one-third of organizations worldwide in a single year, and two-thirds of the victims reported a significant loss of revenue. Payments exceed $600 million in total in 2021, according to a recent report by blockchain data platform Chainalysis.

While the FBI said little on how it got the private key and how it helped Colonial Pipeline retrieve part of the ransom, tracing transactions on the blockchain is becoming an essential part of cybercriminal investigations. Law enforcement agencies often work with analytics companies that have dedicated experts or offer software tools designed to take raw blockchain data and provide insights into it.

"We are able to trace and track the flow of funds in ways that were never possible," says Ari Redbord, head of legal and government affairs at blockchain intelligence company TRM Labs, which provides software to trace cryptocurrency transactions.

Making sense of raw blockchain data can help ransomware victims get some of their money back, but it can also shed light on other types of criminal activities, from that of nation-state actors that operate on the blockchain to any financial fraud or even kidnapping cases.

Often, investigations require weeks of work, niche technical knowledge, and some creativity, but "there's definitely a not insignificant chance of getting at least 25% [of the money back]," says Paul Sibenik, lead case manager at blockchain investigation agency CipherBlade.

Steps in a blockchain investigation

The recovery of the Colonial Pipeline ransom happened under "a very unique circumstance," as Redbord puts it. Still, this DOJ success helped victims learn that getting their funds back could be a possibility. While blockchain investigations can have different lengths, the steps involved are similar, regardless of the type of crime.

When an attack occurs, investigators have the cryptocurrency address the payment was made to. Usually, the money doesn't sit there long. It moves to different addresses, splits into different wallets, and is converted from bitcoin to other cryptocurrency, jumping blockchains. Hackers move funds to cover their tracks but also to pay associates. Some cybercriminal rings use professional money-launderers. All these transactions are broadcast to the blockchain.

"You'll see transaction hashes, you'll see bitcoin and other cryptocurrency addresses, [but] there's no real way to tell how these addresses are linked," says Phil Larratt, the UK operations manager at Chainalysis.

While anyone can access the public ledger and look at the raw data, deriving tangible information from it can be challenging. One way of getting valuable facts is to group addresses together, hoping to identify the entity controlling them, such as individuals, exchanges, or ransomware groups. Individual wallets, for instance, might have five or six addresses, while some services that operate on the blockchain, such as exchanges, might allow for millions of addresses to be grouped together.

Knowing the exact entity behind a batch of addresses can be crucial, and blockchain intelligence companies have ways of finding that. They aggregate information from multiple sources, often using off-chain data to enrich their understanding of transactions. They look at dark web forums, social media posts, and court papers among others.

"You can be on Facebook, and you see [someone] soliciting funds in bitcoin and there's an address there," Redbord says. That address is copied and can be associated with a cybercriminal ring, a terrorist organization, or other illicit entities, depending on the case.

Such nuggets of information are gathered by blockchain intelligence companies and stored for future references. "[We] are building a giant blacklist of cryptocurrency addresses," Redbord adds.

This process of categorizing addresses is done in the background. Investigators using blockchain intelligence software simply input the address corresponding to the payment. Then, they can see the flow of digital money. A valuable piece of information can be, for instance, whether there have been any other payments to that address.

Cybercriminals repeatedly move funds hoping to lose their track, but they must stop at some point. Since there's only so much one can do with bitcoins, they need to convert that money to traditional currency, like U.S. dollars. In some cases, law enforcement can intervene and seize the money as it enters the real world, because most exchanges follow the rules and regulations.

"Law enforcement can get information on who owns that wallet address, or who was associated with that address because they have gotten 'know your customer' information," Redbord says. "That's a major step that law enforcement can take."

Not all exchanges comply. Some, often based overseas, value money more than doing the right thing. "There are plenty willing to facilitate illicit activity or turn a blind eye," Sibenik says. "I don't think exchanges are getting any more compliant."

Recovering ransomware payments

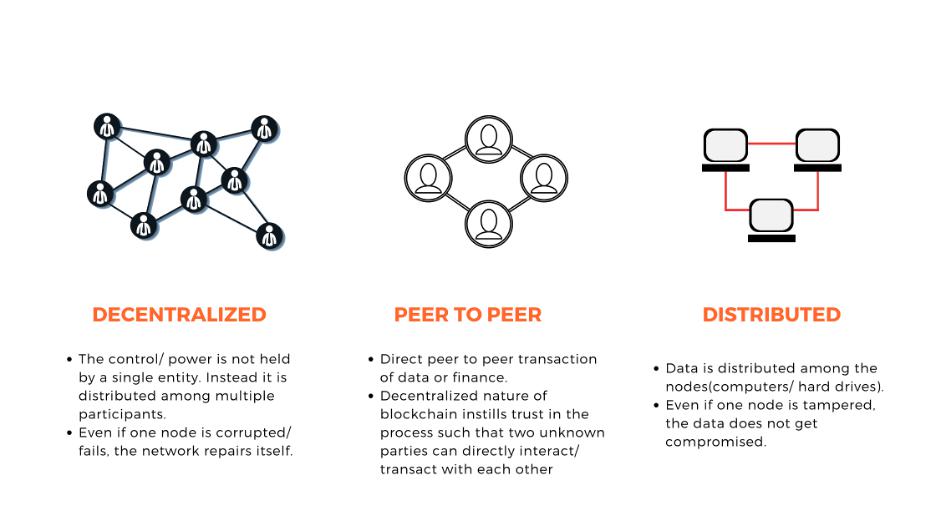

In some cases, organizations that paid the ransom can get at least part of their money back. "With crypto, it is arguably easier to follow the money because every transaction is occurring on an immutable public ledger, where you can see each transaction and then trace the flow of funds," Redbord says.

The chances of recovering the money depend on various parameters, including how much time has passed from the payment to the tentative tracing of the funds, how fast the cybercriminals move the cryptocurrency, what blockchains they use, or whether they use a mixing service. When law enforcement is involved, the chances of success tend to be higher. Blockchain intelligence companies can only provide information, while law enforcement agencies have the power of using subpoenas and other legal processes. "We've seen a lot of successes across different areas," Larratt says.

Still, every case is different, and the chances of recovering the money, at least in part, can vary greatly. Ransomware groups are constantly polishing their skill and have multiplied over the last few years. "Each group may have their own way of laundering the proceeds of crime," Larratt says. "However, because we're at the cutting edge of this technology, we're able to support some of the most sophisticated and complex investigations in relation to ransomware."

Tracing bitcoin transactions is still a complex endeavor, and it should be done by experts. It cannot be done by victims in-house, Sibenik says. "In general, large companies have a difficult time doing incident response work," he adds.

Just another money-laundering scheme

Companies providing blockchain analytics say they are helping to create a trust layer for crypto, and this is beneficial for everyone including exchanges. Redbord, who spent 11 years working as a federal prosecutor at the U.S. DOJ and focused much of that time on threat finance, says that trust should be a core component of any financial system.

"Anti-money-laundering, risk management, and trust are foundational infrastructure," Redbord says. "It's very important to comply with regulations, of course, but ultimately, it may be more important to be building in that trust layer, because people are not going to transact in a financial system that they don't trust."

Larratt hopes, though, that the cryptocurrency industry will also become more regulated, which could potentially curb cybercrime. Since introducing new regulations will likely be a step-by-step process, Chainalysis is putting effort into fine-tuning its software, aiming to support investigators to do their best considering the current conditions. "We're constantly developing new techniques and tools to empower officers and ensure that they can maintain the same sort of quality of investigation in relation to these actors," he says.

At the end of the day, moving cryptocurrency across different addresses "is not really different to money-laundering 15 and 20 years ago, in the fact that funds would be sent to a traditional bank account, and then they'd be cashed out, and then they'd be sent to another bank account, and then funds would be sent overseas," Larratt says.

Experts are optimistic, saying we might see more successful cases in the future. More companies might be able to get at least some of their money back, just like Colonial Pipeline did. "Blockchain analysis, I think, is an essential, but maybe sometimes an underused tactic to help investigate this type of activity," Larratt says.