Household energy use for services such as cooking1 or space heating and cooling2 is crucial for decent living conditions3. Unaffordable energy is a persistent trend4 that is negatively related to social cohesion, climate change responses, and disproportionate environmental impacts on low-income populations and minority groups5. Furthermore, energy inequity is not just a lack of money to meet basic energy needs—it is a lack of access to the capabilities6 that enable a sustainable and prosperous society built on just principles7. Energy inequity could have significant implications for navigating sustainable development and meeting societal goals around decarbonization and energy use. In this study, we demonstrate the magnitude of energy inequity in the United States (US) using a metric informed by Net Energy Analysis (NEA). Without a set of inclusive indicators and data tools to examine energy inequity, many households that are at risk of energy poverty and injustice may remain unidentified. This analysis applies lessons from NEA to address energy poverty in the US.

Many frameworks are currently being explored to understand energy poverty and equity, while differentiating between related concepts. In a thematic exploration of energy equity, Brown et al. identify energy access, energy poverty, energy insecurity, and energy burden as key concepts for understanding the issue8, but quantitative measurement of these concepts has been limited. Pachauri & Rao establish measures for the sustainable development context that incorporate periods when energy is available, the quality of voltage supplied, the reliability in terms of the number of disruptions, the capacity in terms of power available, the consumption levels allowed per day, and affordability of the standard consumption package as a percentage of household income9. Energy metrics have been assessed quantitatively across several countries. Though some aspects, such as formal disconnections from energy service10, are translatable to the US context, these methods require normalizing many variables amongst different types of data and are overly broad for applications in areas where electricity access is relatively high and reliable.

Of such areas, the United Kingdom (UK) has a richer history of incorporating energy poverty formally into its government programs: since 2000, the UK has used some form of an energy burden metric to assess whether households are facing energy poverty and determine the level of support that they require as a result11. This metric has evolved from a simple ratio of household income and energy expenditures to one that incorporates building efficiency ratings and average incomes in the community. While the European Union (EU) currently lacks a unified metric for energy poverty, similar metrics have been developed in member countries, such as a metric which compares incomes and expenditures to local averages and absolute heating needs to determine energy poverty levels in Italy12 or a multidimensional index of building quality and ability to pay bills in Poland13.

Prior research of household prosperity in limited global jurisdictions using these sorts of measures has found that gender, age, housing age14, tenure type15, energy inefficiency16, education, employment17, geography18, socioeconomic status19, race/ethnicity20, and macroeconomic conditions21 are associated with high energy burdens in various geographical areas. The US lags in part due to a lack of metrics and tracking, and this paper develops a tool to show how net energy is a valuable resource to evaluate energy burden and inequality.

In the US, energy inequity is a significant challenge as families struggle to meet monthly bills and live paycheck to paycheck11. There is a growing disparity between wealthier and lower-income households based on their abilities to meet basic energy needs8. While per-unit residential energy prices have increased below the rate of inflation in the US since the 1980s22, many households still struggle to make utility bill payments and are especially vulnerable to economic shocks21.

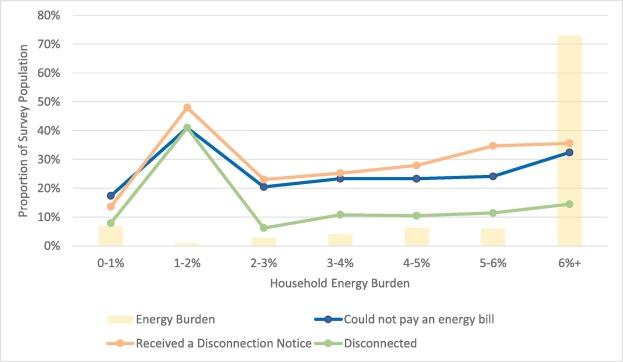

Ross and Drehobl performed distinct urban16 and rural14 analyses to describe energy inequity in the US. While limited by geographic and demographic focus and a lack of peer-review, these studies have established the proportion of income (G) spent on energy expenditures (S), or energy burden (Eb), as the standard benchmark for energy poverty in the US today (Eq. 1). The US Department of Energy (DOE) significantly improved upon Ross and Drehobl’s underlying methodology by assembling its Low-Income Energy Affordability Dataset (LEAD)23, which estimates incomes and energy expenditures for most households in the US at a census-tract scale.

$${{{{{\rm{Energy}}}}}}\,{{{{{\rm{Burden}}}}}}\,({E}_{b})=\frac{S}{G}$$(1)NEA offers potential support to understanding energy equity through the use of formally defined Energy Return Ratios (ERRs) like Eb that articulate the relationships among energy flows within complex systems24. Net Energy Return (NER), which describes the newly released potential to do work as a result of some activity, is recommended as a basis for future analysis25, especially in the study of macro-energy systems like the US residential housing stock26.

Ici, nous examinons la relation entre les dépenses énergétiques et le revenu énergétique des ménages et observons les disparités spatiales à travers une échelle de recensement et le recensement, en particulier dans toute la race et l'ethnicité, le revenu, le mandat du logement et le niveau de scolarité. Une différence de 500 $ en dépenses énergétiques annuelles améliore considérablement la capacité des ménages à revenu moyen et élevé à bénéficier des avantages des services énergétiques à faible coût (2 à 5% du revenu annuel), mais les dépenses énergétiques de base représentent environ 14% des bénéfices annuels pour ménages à faible revenu. Les catégorisations des programmes d'aide fédérale basées sur les indices de pauvreté ne capturent pas au moins 5,3 millions de ménages qui bénéficieraient du soutien et de l'assistance énergétiques. Les ménages des communautés de couleur éprouvent une pauvreté énergétique à un taux de 60% supérieur à ceux des communautés blanches en fonction de cette étude. De plus, l'analyse au niveau de l'État démontre des disparités spatiales plus larges entre les États tels que le Maine, où le pétrole de chauffage résidentiel et le bois de carburant restent des sources d'énergie thermique communes et des États tels que l'Alabama et le Mississippi qui ont en moyenne les rendements énergétiques nets les plus bas. Cette analyse empirique comble une lacune dans la discussion actuelle sur l'équité énergétique en fournissant un cadre pour évaluer les disparités et inclure davantage de ménages dans les mesures de pauvreté énergétique qui sont alignées sur l'évaluation des flux d'énergie à travers des systèmes biologiques, physiques et économiques.