Effects on children, young people

Children and young people presently account for a relatively small portion of direct illness and death from covid-19, although they are not immune and face risks of long covid.17 A narrow focus on the direct and immediate health effects of covid-19 obscures the extent to which the pandemic is affecting children and young people. Each wave of covid-19 infection, illness, and death makes children and young people vulnerable to many negative socioeconomic outcomes (box 1). These negatively reinforce each other and could combine given the long and multiwave nature of the pandemic. Consideration of the multiple effects of the pandemic has prompted the Human Rights Council to request a study on how to mitigate the effect of covid-19 on the human rights of young people.18

The covid-19 related crises affecting children and young people intersect and exacerbate each other. Being orphaned can trigger mental ill health, greater vulnerability to infectious diseases, physical abuse and sexual violence, and poverty.11 Disrupted schooling interferes with access to and delivery of essential health and other services, such as nutritious foods. It increases girls’ vulnerability to child marriage, early pregnancy, and gender based violence, making return to school less likely and HIV infection more likely.1920 Disrupted schooling also causes parents, especially mothers, to leave work to provide care, reducing income which could support children and young people.21 In undermining the development of children and young people, such effects have profound consequences for societies. In December 2021, the World Bank, Unesco, and Unicef warned that the learning crisis alone could result in $17tn (₤12.5tn) in lost lifetime earnings at present value globally.22

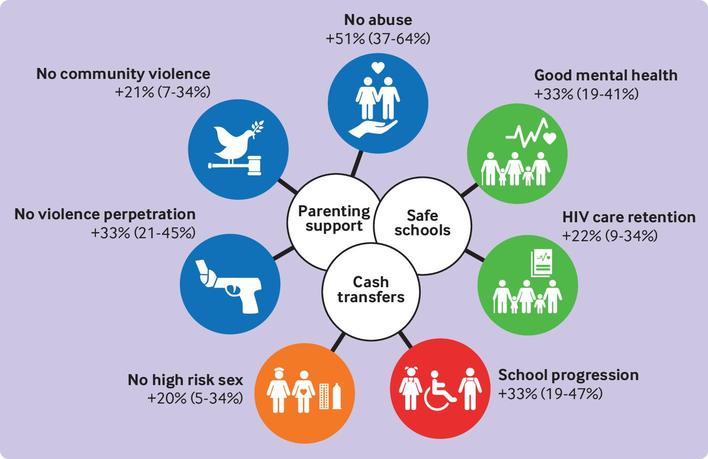

Children and young people in lower income countries will be most adversely affected by covid-19 because of inequities in covid-19 vaccination, fiscal capacity to respond, and social protection coverage. As of 12 January 2022, just 11.4% of people in low income countries had received at least one covid-19 vaccine dose compared with 67.6% in high income countries.23 At a time when over 60% of low and middle income countries are highly vulnerable to debt,24 poorer countries would need to add hundreds of millions of dollars to their existing public debt to cover the cost of vaccinating 70% of their population.23 Even if they were able to do this, it could compromise investment in other measures to protect children and young people, such as healthcare and nutrition. Furthermore, while the pandemic has driven unprecedented investment in emergency social protection measures, 87% of social spending from March 2020 to May 2021 was by high income countries, compared with just 4.7% by low and middle income countries. Income support programmes appear to have mitigated overall increases in poverty in upper middle income countries, at least temporarily, but have been insufficient to do so in low income countries.25 More than four billion people, including three in four children, still lack any social protection such as support grants or bursary schemes.26