Each new Wi-Fi standard has brought significant improvements in performance, with the most recent, 802.11ac, offering an impressive theoretical maximum rate of 1.3Gbps. Unfortunately, these gains have not been enough to keep pace with demand, leading to that exasperated cry heard across airports, malls, hotels, stadiums, homes and offices: “Why is the wireless so slow?”

The IEEE is taking another crack at boosting Wi-Fi performance with a new standard called 802.11ax or High-Efficiency Wireless, which promises a fourfold increase in average throughput per user.

RELATED:

Can MU-MIMO really boost wireless capacity?

802.11: Wi-Fi standards and speeds explained

Wi-Fi 2018: What does the future look like?

802.11ax, which is known as Wi-Fi 6 under a new naming convention, is designed specifically for high-density public environments, like trains, stadiums and airports. But it also will be beneficial in Internet of Things (IoT) deployments, in heavy-usage homes, in apartment buildings and in offices that use bandwidth-hogging applications like videoconferencing.

802.11ax is also designed for cellular data offloading. In this scenario, the cellular network offloads wireless traffic to a complementary Wi-Fi network in cases where local cell reception is poor or in situations where the cell network is being taxed.

Excitement surrounding the new standard is high. Even though the 802.11ax is not expected to be finalized until early 2019, the vendor community is chomping at the bit. Pre-standard chipsets have been shipping since last year and the first 802.11ax routers are currently hitting the market. In a typical Wi-Fi deployment scenario, early adopters are comfortable using pre-standard products, which readily win certification from the Wi-Fi Alliance after they fully comply with the standard with a firmware upgrade.

What problem is 802.11ax trying to solve?

The fundamental problems with Wi-Fi are that bandwidth is shared among endpoint devices, access points can have overlapping coverage areas, especially in dense deployments, and end users can be moving between access points.

The current solution, based on a technology from the old shared Ethernet days called Carrier Sense Multiple Access with Collision Avoidance (CSMA/CA), requires endpoints to listen for an all-clear signal before transmitting. In the event of interference, congestion or collision, the endpoint goes into a back-off procedure, waits for the all-clear, then transmits.

In a crowded stadium, a busy airport or a packed train with hundreds, even thousands, of end users attempting to stream video at the same time, the system loses efficiency and performance suffers.

The good news is that 802.11ax promises improved performance, extended coverage and longer battery life. 802.11ax can deliver a single stream at 3.5Gbps, and with new multiplexing technology borrowed from the world of LTE cellular, can deliver four simultaneous streams to a single endpoint for a total theoretical bandwidth of an astounding 14Gbps.

How does 802.11ax work?

The 802.11ax standard takes a variety of well-understood wireless techniques and combines them in a way that achieves a significant advance over previous standards, yet maintains backward compatibility with 802.11ac and 802.11n.

802.11ax delivers a nearly 40 percent increase in pure throughput thanks to higher order QAM modulation, which allows for more data to be transmitted per packet. It also achieves more efficient spectrum utilization. For example, 802.11ax creates broader channels and splits those channels into narrower sub-channels. This increases the total number of available channels, making it easier for endpoints to find a clear path to the access point.

When it comes to downloads from the access point to the end user, early Wi-Fi standards only permitted one transmission at a time per access point. The Wave 2 version of 802.11ac began using Multi-User, Multi-Input, Multiple Output (MU-MIMO), which allowed access points to send up to four streams simultaneously. 802.11ax allows for eight simultaneous streams and makes use of explicit beamforming technology to aim those streams more accurately at the receiver’s antenna.

Even more importantly, 802.11ax piggybacks on MU-MIMO with an LTE cellular base station technology called Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA). This allows each MU-MIMO stream to be split in four additional streams, boosting the effective bandwidth per user by four times.

The way Network World columnist Zeus Kerrevala explains

802.11ax

, early Wi-Fi was like a long line of customers in a bank waiting for one teller. MU-MIMO meant four tellers serving four lines of customers. OFDMA means each teller can simultaneously serve four customers.

How is 802.11ax different from 802.11ac?

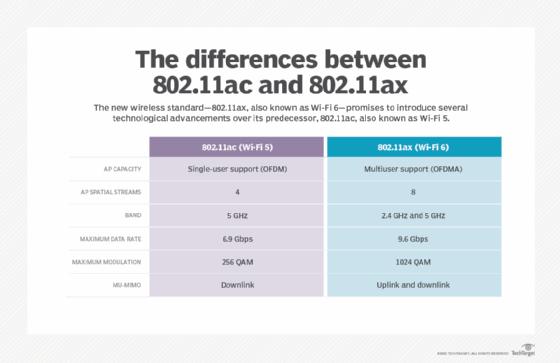

802.11ac operates in the 5Ghz range only, while 802.11ax operates in both the 2.4Ghz and 5Ghz ranges, thus creating more available channels. For example, early chipsets support a total of 12 channels, eight in the 5Ghz and four in the 2.4Ghz range.

With 802.11ac, MU-MIMO is limited to downlink transmissions only. 802.11ax creates MU-MIMO connections so that with downlink MU-MIMO an access point may transmit concurrently to multiple receivers and with uplink MU-MIMO an endpoint may simultaneously receive from multiple transmitters.

802.11ax supports up to eight MU-MIMO transmissions at a time, up from four with 802.11ac. OFDMA is new with 802.11ax, as are several other technologies, like trigger-based random access, dynamic fragmentation and spatial frequency re-use, all aimed at improving efficiency.

Finally, 802.11ax introduces a technology called “target wake time” to improve wake and sleep efficiency on smartphones and other mobile devices. This technology is expected to make a significant improvement in battery life.

When will we see 802.11ax products and adoption?

Quantenna Communications was first out of the gate, announcing the first 802.11ax silicon in October 2016. The chipset supports eight 5GHz streams and four 2.4 GHz streams. In January 2017, Quantenna added a second chipset to its portfolio with support for four streams in both bands.

Other Wi-Fi chipset vendors have followed suit. Qualcomm announced their first 802.11ax silicon in early 2017, followed by Broadcom and Marvell.

The first 802.11ax router was introduced by Asus last August. Using Broadcom silicon, the Asus router has 4×4 MIMO in both bands and achieves a maximum throughput of 1.1Gbps on 2.4 GHz and 4.8 Gbps on 5 GHz.

Huawei has announced an 802.11ax access point that uses 8×8 MIMO and is based on Qualcomm hardware. And in January, Aerohive Networks announced its first family of 802.11ax access points based on Broadcom chipsets. These are expected to start shipping mid-2018.

The IEEE approved 802.11n in 2007 and 802.11ac in 2013, so they’re sticking with the six-year interval when it comes to 802.11ax. A draft 802.11ax standard is expected to be published in the first quarter of 2018, with the final standard wrapping up in Q1 2019.

Interim Wi-Fi certification of 802.11ax gear by the Wi-Fi Alliance will begin in the fourth quarter of this year, with volume production of 802.11ax products expected to ramp up next year.

In terms of mass adoption, we’re probably talking 2020, but forward-thinking IT execs, especially those running high-density Wi-Fi networks, should launch 802.11ax pilot projects this year.

(Neal Weinberg is a freelance technology writer and editor. He can be reached at

neal@misterwrite.net

.)

Join the Network World communities on

and

to comment on topics that are top of mind.