“It’s a lot to listen to a robot all day long,” said Tina Pinedo, communications director at Disability Rights Oregon, a group that works to promote and defend the rights of people with disabilities.

But listening to a machine is exactly what many people with visual impairments do while using screen reading tools to accomplish everyday online tasks such as paying bills or ordering groceries from an ecommerce site.

“There are not enough web developers or people who actually take the time to listen to what their website sounds like to a blind person. It’s auditorily exhausting,” said Pinedo.

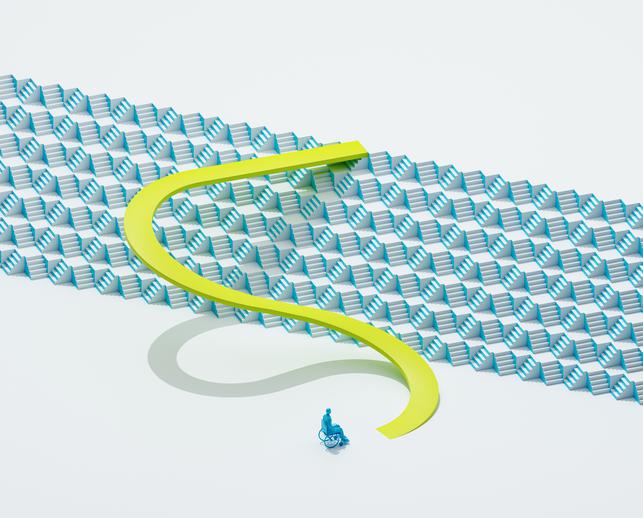

Whether struggling to comprehend a screen reader barking out dynamic updates to a website, trying to make sense of poorly written video captions or watching out for fast-moving imagery that could induce a seizure, the everyday obstacles blocking people with disabilities from a satisfying digital experience are immense.

Needless to say, technology companies have tried to step in, often promising more than they deliver to users and businesses hoping that automated tools can break down barriers to accessibility. Although automated tech used to check website designs for accessibility flaws have been around for some time, companies such as Evinced claim that sophisticated AI not only does a better job of automatically finding and helping correct accessibility problems, but can do it for large enterprises that need to manage thousands of website pages and app content.

Still, people with disabilities and those who regularly test for web accessibility problems say automated systems and AI can only go so far. “The big danger is thinking that some type of automation can replace a real person going through your website, and basically denying people of their experience on your website, and that’s a big problem,” Pinedo said.

Why Capital One is betting on accessibility AI

For a global corporation such as Capital One, relying on a manual process to catch accessibility issues is a losing battle.

“We test our entire digital footprint every month. That’s heavily reliant on automation as we’re testing almost 20,000 webpages,” said Mark Penicook, director of Accessibility at the banking and credit card company, whose digital accessibility team is responsible for all digital experiences across Capital One including websites, mobile apps and electronic messaging in the U.S., the U.K. and Canada.

Accessibility isn’t taught in computer science.

Even though Capital One has a team of people dedicated to the effort, Penicook said he has had to work to raise awareness about digital accessibility among the company’s web developers. “Accessibility isn’t taught in computer science,” Penicook told Protocol. “One of the first things that we do is start teaching them about accessibility.”

One way the company does that is by celebrating Global Accessibility Awareness Day each year, Penicook said. Held on Thursday, the annual worldwide event is intended to educate people about digital access and inclusion for those with disabilities and impairments.

Before Capital One gave Evinced’s software a try around 2018, its accessibility evaluations for new software releases or features relied on manual review and other tools. Using Evinced’s software, Penicook said the financial services company’s accessibility testing takes hours rather than weeks, and Capital One’s engineers and developers use the system throughout their internal software development testing process.

It was enough to convince Capital One to invest in Evinced through its venture arm, Capital One Ventures. Microsoft’s venture group, M12, also joined a $17 million funding round for Evinced last year.

Evinced’s software automatically scans webpages and other content, and then applies computer vision and visual analysis AI to detect problems. The software might discover a lack of contrast between font and background colors that make it difficult for people with vision impairments like color blindness to read. The system might find images that do not have alt text, the metadata that screen readers use to explain what’s in a photo or illustration. Rather than pointing out individual problems, the software uses machine learning to find patterns that indicate when the same type of problem is happening in several places and suggests a way to correct it.

“It automatically tells you, instead of a thousand issues, it’s actually one issue,” said Navin Thadani, co-founder and CEO of Evinced.

The software also takes context into account, factoring in the purpose of a site feature or considering the various operating systems or screen-reader technologies that people might use when visiting a webpage or other content. For instance, it identifies user design features that might be most accessible for a specific purpose, such as a button to enable a bill payment transaction rather than a link.

Some companies use tools typically referred to as “overlays” to check for accessibility problems. Many of those systems are web plug-ins that add a layer of automation on top of existing sites to enable modifications tailored to peoples’ specific requirements. One product that uses computer vision and machine learning, accessiBe, allows people with epilepsy to choose an option that automatically stops all animated images and videos on a site before they could pose a risk of seizure. The company raised $28 million in venture capital funding last year.

Another widget from TruAbilities offers an option that limits distracting page elements to allow people with neurodevelopmental disorders to focus on the most important components of a webpage.

Some overlay tools have been heavily criticized for adding new annoyances to the web experience and providing surface-level responses to problems that deserve more robust solutions. Some overlay tech providers have “pretty brazen guarantees,” said Chase Aucoin, chief architect at TPGi, a company that provides accessibility automation tools and consultation services to customers, including software development monitoring and product design assessments for web development teams.

“[Overlays] give a false sense of security from a risk perspective to the end user,” said Aucoin, who himself experiences motor impairment. “It’s just trying to slap a bunch of paint on top of the problem.”

In general, complicated site designs or interfaces that automatically hop to a new page section or open a new window can create a chaotic experience for people using screen readers, Aucoin said. “A big thing now is just cognitive; how hard is this thing for somebody to understand what’s going on?” he said.

Even more sophisticated AI-based accessibility technologies don’t address every disability issue. For instance, people with an array of disabilities either need or prefer to view videos with captions, rather than having sound enabled. However, although automated captions for videos have improved over the years, “captions that are computer-generated without human review can be really terrible,” said Karawynn Long, an autistic writer with central auditory processing disorder and hyperlexia, a hyperfocus on written language.

“I always appreciate when written transcripts are included as an option, but auto-generated ones fall woefully short, especially because they don't include good indications of non-linguistic elements of the media,” Long said.

Lawsuit threats — or the right thing to do?

Some companies that make accessibility overlay software take a blunt approach to selling it: The threat of lawsuits. “There was a time when it was possible to get away with having a website that didn’t work for people with disabilities. But those days are long gone, and ADA regulations for web accessibility are being enforced in court,” states UserWay on its website, noting that its “AI-powered” software is “the easiest way to avoid lawsuits.”

Much like in the digital privacy technology sector, the conversation around digital accessibility tech often emerges through a prism of legal threats and regulatory compliance, while incentives such as helpfulness and inclusion get less attention.

AccessiBe’s homepage touts its tech as “The #1 Automated Web Accessibility Solution” for regulatory compliance. Evinced, on the other hand, seems to play down the compliance-related selling points. Its homepage slogan? “Doing the right thing just became a lot easier.”

“It makes good financial sense to do this outside of a compliance risk perspective. Disabled customers are incredibly loyal,” said Aucoin.

However, concerns about legal risks are warranted. There were nearly 27% more lawsuits related to digital accessibility filed in the last quarter of 2021 compared to the last quarter of 2020, according to Accessibility.com, a website providing digital accessibility information that tracks accessibility lawsuits in state and federal jurisdictions throughout the U.S. and is funded through sponsorships from digital accessibility businesses. According to the site’s 2021 report, 2,352 web accessibility lawsuits were filed in 2021, up from 2,058 cases filed nationwide in 2020.

While legal threats mount, the pandemic spurred on additional pressure from federal regulators. The Department of Justice published guidance in March reminding businesses that web accessibility for people with disabilities is “a priority,” and that the agency is watching to see that companies ensure digital services are accessible to everyone, including digital public health services.

The DOJ highlighted recent settlements with grocery and pharmacy chains including Hy-Vee, Kroger, Meijer and Rite Aid, all of which the agency claimed violated the Americans with Disabilities Act by failing to make their COVID-19 vaccination registration portals accessible to some people with disabilities, including those who use screen reader software.

The Justice Department has emphasized its position that the ADA’s requirements apply to all services and activities of state and local governments — such as applying for an absentee election ballot or filing taxes — as well as online public accommodations such as ordering food or buying other goods or services.

The World Wide Web Consortium, the global body that establishes technical standards for the internet, has updated its Web Content Accessibility Guidelines over the years. Those standards “allowed for tech companies to say, ‘We can automate this — all you have to do is run scripts now based on those guidelines,’” said Lina Rivera, associate director of Quality Assurance at Rapp, a digital creative marketing agency.

However, Rivera said, those guidelines should be just the starting point. “What is not being said here? What is not being covered? Having those conversations with the different communities impacted by these guidelines is [what’s needed],” Rivera said.

The human touch

Rivera and the QA team at Rapp use automated tools to test marketing emails and websites the agency produces for advertisers, including tools that evaluate how emails will be read by screen readers.

But there are limits to the efficacy of simply automatically turning off animations or checking for image alt tags in webpage code, accessibility experts say. “Automation can only do so much,” Aucoin said. For example, he said although an automated tool might detect that code includes alt text language so screen readers can verbalize what’s in an image, “We can’t say if it is a good description.”

Rather than relying on its web development coders to write alt text, Rapp’s creative team has been involved over the past year in writing copy for use in descriptive image code in order to provide a better experience for visually impaired people, Rivera said. “We created an alt text guide,” she added.

Even champions of AI-based tech for accessibility recognize the need to involve people in the process.

“There’s always a role for manual testing,” said Penicook, who said his group at Capital One conducts manual tests and monitors existing webpages and content. Assistance from tools like Evinced’s software allows his team to cover more bases, faster, he said.

“Testing for accessibility is not a straightforward thing at all. It has to be a combination of manual and automated,” said Rivera.

Pinedo said companies should be receptive to reviews people with disabilities give about their digital experiences, too, and be open to making relevant changes.

“There’s no way to anticipate people with multiple types of disabilities that may be using older types of [screen readers or computers],” she said. “The best thing you can do is to have an accessibility statement and be receptive to when something isn’t accessible to people in some way.”