PITTSBURGH — In his 22 years at Amazon, including his role as the first CEO of the company’s Worldwide Consumer business, Jeff Wilke always kept the place he was raised, and the people he grew up with, in the back of his mind.

“I always wanted to lead in a way that if I went back, and people from high school could ask me anything about what I was encountering, the decisions I made, how I made them, that they’d be proud of me,” Wilke said.

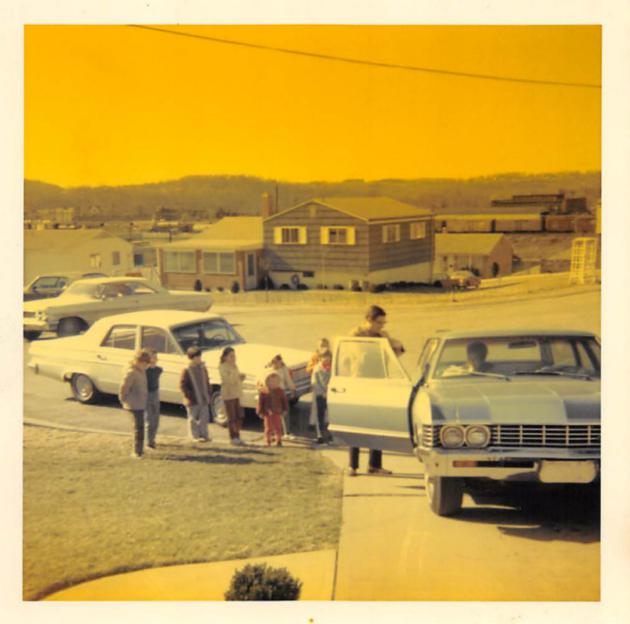

Born at Allegheny General Hospital in 1966, Wilke grew up in the community of Green Tree, Pa., just outside of Pittsburgh. He wore flannel shirts to class at the public high school, Keystone Oaks, and played baseball in the shadow of the water tower still visible from the Parkway on the drive into the city.

In addition to shaping his values as a leader, his hometown gave him a first-hand view of the decline of the steel industry that had put Pittsburgh at the center of the industrial revolution.

“It was both a cloudy and a smoky city in the early 70s,” he said. “A lot of that changed as the industry moved, but of course the industry movement was so catastrophic that it left behind a different kind of cloudiness that took some time to shine away.”

In the decades that followed, Pittsburgh’s role in the rise of robotics and artificial intelligence have made the city an emblem of U.S. resilience and reinvention.

Wilke left in 1985 for college at Princeton University, but he still gets together every year with a group of his childhood friends. His family’s legacy is still visible in the nearby community of Sheridan, Pa., at the former home of his grandfather’s business, the G.C. Wilke Garage, where the sign is still on the building.

During Amazon’s search for a second headquarters, Wilke’s personal history and love for Pittsburgh generated speculation that he might end up tipping the scales in the favor of his hometown.

Of course, that didn’t turn out to be the case, as Amazon chose New York City and Eastern Virginia for its HQ2, before dropping the New York plans after encountering opposition there. Wilke said he ensured that Pittsburgh was on the list for consideration, but also made sure not to let his strong feelings for the city bias the ultimate decision.

Since leaving Amazon last year, Wilke has returned to his industrial roots as the chairman and co-founder of Re:Build Manufacturing, a Massachusetts-based company seeking to revive the U.S. manufacturing industry. Re:Build has made nine acquisitions, in areas including engineering services and advanced materials, with 600 employees in eight states.

We caught up with Wilke as part of GeekWire’s recent return to Pittsburgh, talking about his upbringing and history in the city, and his outlook for the future of robotics, AI, automation and U.S. manufacturing.

Listen below, and continue reading for highlights, edited for clarity and length.

Q: Pittsburgh in the ’60s and the ’70s — how would you describe the place?

Wilke: Well, it was going through a time of transition. I don’t remember the ’60s, really. My first memory of Pittsburgh was the day that Roberto Clemente died [Dec. 31, 1972]. He had hit his 3,000th hit. It was a really oddly warm winter day, and my brother and I were playing T-ball in the little circle at the end of the street.

And my grandfather was there, I think, and somebody came out of the house and gave the news. It’s one of those moments that froze because I was totally into baseball. I’d fall asleep listening to Bob Prince call the games at night and it just kind of hit me. [Clemente] was the first person that I cared about that had passed away.

I almost remember the color of the sky. In Pittsburgh at that time, there was still a lot of industry. It was both a cloudy and a smoky city in the early ’70s. A lot of that changed as the industry moved, but of course, the industry movement was so catastrophic that it left behind a different kind of cloudiness in the city that took some time to shine away.

The steel industry, especially, but all of the industry that was there was so tightly bound with the community, and I was awed by it. We would drive by the rusting steel mills, every time our family drove to Kennywood, local amusement park. So many of my memories are from this place, it’s crazy. It’s got these old wooden roller coasters that are actually pretty killer.

But Pittsburgh was a sad place. And the mood of despair was really lifted in the mid ’70s by the rise of the Steelers dynasty. I think one of the reasons that Steelers fans, my age at least, are so loyal is that no matter where in the world they live, they just remember how deeply they felt, that this team was able to lift the spirits of the entire town. It was something for people to rally around and feel proud of. And that left an indelible mark. So I’ll be a Steelers fan for the rest of my life.

Are there personality traits of yours, characteristics of your approach to life, that you can trace back to the environment that you grew up in?

I met really good people in Pittsburgh. And they inspired me in school. My high school was a public school where most kids weren’t focused on a four-year college, but the teachers there really cared, and I learned to love math and chemistry, and especially computers.

I had this elementary school teacher who introduced us to computing through a dial-up modem that was connected to one of Carnegie Mellon’s mainframes. … Just communicating with a computer like that, it froze in my memory. And then I had a couple of other teachers along the way who introduced me to some more complicated things in that space. Super grateful for that.

I met lifelong friends there. I think some people will leave their home and never want to go back. They reinvent themselves. And for me, I still get together every year with a half-dozen childhood friends that have gone to different places. Some of them live there, and the thread that’s through all of these people is that they taught me that what mattered most was how you treated others, not where you fell in any particular pecking order.

I had a great mentor years ago who reminded me that followers choose their leaders. And I think followers want to choose people who treat them with respect and dignity, and who are authentic with them. I’ve made a ton of mistakes along the way, but the part that has resonated with followers has probably come from the authenticity that I learned in Pittsburgh.

What were the ingredients that enabled Pittsburgh to have this new life beyond the steel mills?

I start by thinking about the families in the last wealth-generation period. Oil was discovered in Oil City in the late 1800s, just north of Pittsburgh, which was the beginning of that epoch. So they had oil, technology, and money and banking that came from that, and steel, and then ultimately medicine, computing, AI, robotics.

And in that first wave of entrepreneurialism and wealth creation, Pittsburgh had the extraordinary generosity of the Carnegies, the Mellons, the Fricks, the Schenleys, the Hillmans, the Heinzes, the Falks, the Kaufmans. All these people poured their fortunes back into the city, and they did it into the city proper, into the downtown.

So when you see Heinz Hall, when you see all of the art venues, when you see the museums, I think for its size, Pittsburgh punches way above its weight on culture that’s available to everybody, and that was the whole idea. Carnegie’s whole idea of the library and museum was to make all of this knowledge available to as many people as possible from whatever walk of life they came, and it was pretty visionary.

Building that into the fabric of the city in the early 1900s, and then having the long view that universities invariably provide. So having both Pitt and CMU in a relatively smaller city, coupled with this cultural wealth, it allowed it to ride out troughs along the way.

They made a couple of architectural mistakes. There’s a great book called “Smoketown” that traces the history of, among other things, the Black community in Pittsburgh, which was thriving. And unfortunately when they built the Civic Arena, they razed a whole bunch of that cultural area. So it had moments where it wasn’t its best self, but it always pulled through for the long run, unlike some of the cities in the Midwest that weren’t able to do that.

How would you compare and contrast Pittsburgh with Seattle and Silicon Valley? As you’re talking about the philanthropists that were so prominent in Pittsburgh, I can’t help but think of Bill Gates and Paul Allen and the different approaches they took. Bill Gates has taken a global approach, whereas Paul Allen, frankly, mirrored more closely what you’re talking about in Pittsburgh.

Well, Seattle and Pittsburgh have a lot in common. They both have great universities. They’ve both been powered by immigrant communities and by industry. They’re both, at their core, blue-collar towns. Although Seattle is a tech town now, but it’s both, actually.

I gave a little talk to the Seattle Chamber some years ago and I drew this comparison, and I think there were some folks in the audience who understood the comparison. But some were like, “Pittsburgh? What are you talking about? We’re a tech town.” Well, Pittsburgh is, too. Like Pittsburgh, Seattle’s been reborn a bunch of times.

You mentioned the Allen family. There are the families that built PACCAR and Nordstrom and Boeing and Costco and Alaska Airlines and Weyerhaeuser and Amazon, and all of them cared about the city, and endowed its arts and learning in a way that punches above its weight.

Unfortunately, both have about the same number of sunny days. Not nearly enough. There’s a reason that I was comfortable with the weather when I got to Seattle.

But here’s the biggest similarity between Pittsburgh and Seattle in my view, and the biggest difference between those two versus Silicon Valley: Silicon Valley has way more swagger than Seattle or Pittsburgh. It just does. All three of them are tenacious, but I found a special kind of humility in Pittsburgh that I often found in Seattle, too.

You’re now focused in part on manufacturing through your role with Re:Build Manufacturing. Is there a chance for Pittsburgh to essentially reconnect with its roots as manufacturing attempts to come back to the U.S., through the implementation of automation and robotics?

I think that’ll play a role. I think robotics and AI are necessary in bringing manufacturing back, including to Pittsburgh, but they’re not sufficient. We’re going to need robotics and AI to complement skilled humans who are going to work alongside them. And more and more I’m thinking this way.

I was just at Erik Brynjolfsson‘s Digital Economy Lab advisory board over the last couple days. And he used these words: complement versus substitute. And I really like them. I think that is the model. He’s been writing about this for a while, but I think he’s right that we need to think about them as complementing human work, complementing skilled humans, making work better, making human work more fulfilling, more valuable. I don’t think it’s going to substitute for all human work.

But it’s not enough. U.S. manufacturing companies need to get more serious about computer science. Not just robotics and AI as part of computer science, but computer science more broadly. And that includes the design of products with software built into them, utilizing software for product and process design.

And they’re not there yet. Most manufacturers that I’ve met over the last year and a half have treated computer science as a third-class engineering discipline. “We do electrical engineering, we do chemical engineering, we do mechanical engineering, we do material science.” And I think they need to say, “We do computer science.”

To bring manufacturing more fully back, we’re going to need to use technological advances beyond those fields, though. We’re going to need material science advancements, process design advancements, bioengineering. The cool thing is, all these operational excellence tools — like lean, defect reduction, theory of constraints, Six Sigma defect reduction — these things help build Amazon. And they’re going to help rebuild the capability to be a world class manufacturer with the right cost and quality in the U.S., and the good news they haven’t left completely.

I’m super excited about the opportunity ahead. I’m an optimist about most things. Yes, there are a lot of challenges. Yes, the supply chain is tough. Yes, there’s inflation that’s partly driven by some of the challenges we’re seeing in supply chain, among other things. And these make it really tough right now for a lot of people.

But I think when we get through this, we have the opportunity to create all kinds of advantage for Americans that will persist for a long time.

We spoke with you and Re:Build Manufacturing CEO Miles Arnone last year. Catch us up on where Re:Build Manufacturing is today?

Well, I’m super excited about it. Lots of progress. We completed our ninth acquisition earlier this year. So we now have over 250 engineers. We have 600 employees in eight states and we’ve started to really zero in on our areas of focus.

We’re trying to support customers and designing products in a couple of areas: reducing weight through really innovative materials like composites instead of metals, and supporting electrification. As we decarbonize by electrifying the grid, there’s such an opportunity to make components and sub-components, and finished product across a whole range of industries.

We’re focused on mobility. So everything from scooters to new aircraft designs and enabling satellites and space launches to be more effective.

And then the last thing we got into with a couple of the latest acquisitions is medical devices.

The Re:Build Way, which is our set of leadership principles, continues to define the culture, and it’s turning out to be really valuable as a way to make sure that, as we get bigger, we keep the culture consistent.

Our biggest challenge right now is hiring enough skilled people, everybody from people on the shop floor to engineers. But I think with the right culture, right leadership, we’ll find those people and they’ll be glad they came.

Thinking ahead, how would you describe Pittsburgh’s potential in the years to come? And what are the challenges that the city and its leaders will need to overcome to achieve that potential?

Well, I think it has a really bright future. We’ve talked a little bit about how technology may evolve, and manufacturing. If we go back to the things that sustained Pittsburgh through the challenges that it’s had over the years, going back to the ’70s, a lot of it is the strong universities, the terrific civic infrastructure, really low cost of living, and now a highly skilled workforce. And I think you put all that together and it really bodes well for the city’s future.

I hope it maintains its humility, because I think that’s a very special thing about Pittsburgh. And you know, I don’t know that with a bunch of outsiders coming in that it wouldn’t change. But in addition to being humble, it also has to continue to be bold and make investments in new technologies and supporting industries of the future. And I think Pitt, CMU, all the other local colleges will be vital in steering those investments.

And I really do think it’s already on a path to repair and exceed the losses that it suffered during the ’70s. And I am sure as heck going to be rooting for it along the way.